Algeria sends medical aids to Ghat and Ubari in Libya

MELLITAH TERMINAL, Libya—A 9-foot-high wall built of fabric, sand and steel that can withstand a car bomb surrounds this seaside oil-and-gas complex, a barrier against militant attacks that many in Libya hope will soon be fortified by a national army under a central command.

Two rival factions that have spent years fighting for control of Libya are now locked in a political battle to form a unity government capable of defending their country and its oil industry against escalating attacks by Islamic State.

The political standoff has swelled U.S. worries of Libya turning into a hub for international Islamic State operations. Top national security advisers met last week with President Barack Obama over Islamic State as military leaders increasingly point to the need for stepped-up operations against the militant group, including in Libya.

Libya’s National Oil Co., among the country’s last functioning institutions since the fall of dictator Moammar Gadhafi in 2011, issued a “cry for help” last month amid killings, car bombings, gas line sabotage and the burning of oil storage tanks by extremists. The attacks appeared aimed at undermining the peace process and Libya’s oil industry, which supplies 95% of state revenues.

Islamic State “fills the void” left by the lack of a unified government, said Fathi Ali Bashaagha, a Libyan lawmaker helping negotiate a United Nations-brokered power-sharing agreement between the two rival factions. Libya’s fight against extremists has fallen largely to militias with varying allegiances.

The government talks, which have dragged for months, gained new urgency for Libya and the West with the stepped-up assaults. The U.S., which has conducted drone surveillance in Libya, said last week a small group of U.S. military personnel in Libya has been collecting intelligence and coordinating assistance.

Wait and see

The Obama administration, concerned for months about the threat posed by Islamic State in Libya, has, along with European allies, taken a wait-and-see approach as it awaits formation of a unity government.

“Right now, the international community has no government to work with,” said Mr. Bashaagha, the Libyan lawmaker. “We have only one key and if we lose this key, we lose everything.”

A newly empowered Libyan parliament took halting steps toward peace last week, voting to accept formation of the U.N.-brokered unity government that unites the two factions that have split the country. But the parliament also rejected creation of a 32-member cabinet and set a deadline of Feb. 4 for agreement on a cabinet made up of fewer government ministers.

The U.N. envoy to Libya, Martin Kobler, said last week that changes could be made to the peace agreement to bring the sides together.

European Union foreign ministers have said over the past year they may target with sanctions those who stand in the way of an agreement. The EU’s 28 member states could decide on an asset freeze and travel ban as early as Monday, targeting members of the factions engaged in violence and refusing to abide by the U.N. deal.

At stake are Libya’s 47 billion barrels of crude reserves, the largest in Africa and the source of virtually all of the country’s wealth. “We can stabilize,” said Mustafa Sanallah, the chairman of Libya’s National Oil Co. “Or we can descend into chaos.”

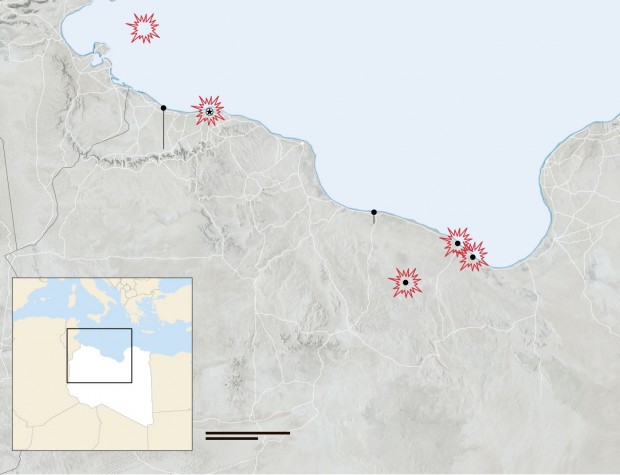

Hot Spots

In the past year, the Islamic State has been using its stronghold of Sirte to launch attacks on oil facilities.

Islamic State has tightened its grip on the city of Sirte, a port connecting with Libya’s so-called oil crescent on the central coast and the only territory held by the extremist group outside of Syria and Iraq.

“They will be looking to seize more here, and look for more ways to fund their operations and taking the oil ports and fields in east Libya would be a very big win for them, one we can’t afford,” said Ismail Shoukry, Libya’s head of military intelligence for the region that includes Sirte.

Islamic State last month launched attacks in Ras Lanuf, about 400 miles east of Tripoli, setting fire to oil-storage tanks and severing a gas line that supplied cities to the west, a security official said. Earlier in the month, attackers used machine guns and car bombs in Ras Lanuf and the nearby port city of Es Sider. The assaults killed at least 10 guards and set on fire at least seven tanks at both facilities, Libyan officials said.

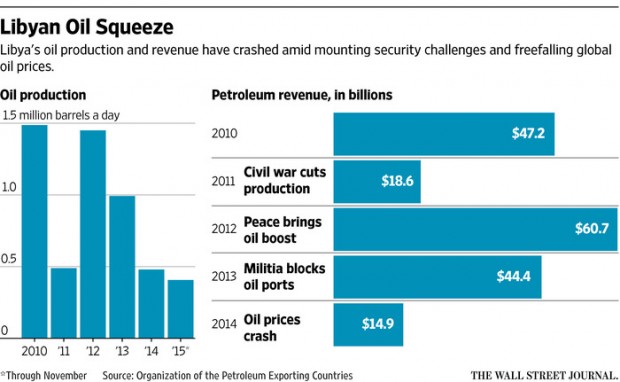

The Islamic State attacks hamper an already struggling oil industry. Libya produces about 400,000 barrels a day, a quarter or so of its capacity.

The extremist group has urged recruits to head to Libya to help form a militant base with strategic proximity to Europe. Libya is a launching point for migrants headed to Italy, giving Islamic State access to the human-smuggling network. The country also supplies Europe with oil and natural gas.

Attacks on Libyan oil facilities test the ability of Islamic State to spread beyond its strongholds in Syria and Iraq, where it has seen recent setbacks.

“The control of the Islamic State over this region will lead to economic breakdowns especially for Italy and the rest of the European states,” Islamic State’s leader in Libya, Abul Mughirah al Qahtani, told the group’s magazine last fall. He was killed in November in a U.S. drone strike, the first Islamic State militant successfully targeted outside of Iraq and Syria, officials said.

Conflict between rival militias has also posed problems for oil production. An Islamist-leaning government has operated out of the capital Tripoli in the western half of Libya. A rival government is based in the eastern city of Bayda. Those two sides clashed violently until the U.N.-brokered agreement was reached in December.

The peace agreement calls for creation of a national army, as well as placing the central bank and national oil company under control of the new central government.

Competing factions

The council responsible for forming a cabinet is working to pare down a 32-ministry government that was rejected by parliament a week ago. The proposed cabinet was larded with redundant ministries, reflecting the difficulty of forming an inclusive government from Libya’s competing political and military factions.

In the absence of a central military command or national police force, many Libyan oil facilities fall under the protection of the Petroleum Facility Guard, a loosely knit group under the direction of militia leaders around the country. “We need help on the ground,” said Mohamed Boubagousha, a guard official in the eastern oil port of Sidra.

The 9-foot-high wall that surrounds the Mellitah Oil and Gas Complex, on the Mediterranean coast in Libya’s northwestern corner, is large enough to encircle Central Park in New York City. It was built last summer after Islamic State opened training camps about 12 miles east.

Western and Libyan security officials believe Islamic State plans to attack Mellitah from an encampment about 12 miles away in palm groves near the town of Sabratha. Workers at the oil-and-gas complex said the facility was prepared for any assault.

“We have to be ready for the worst,” said Mayuf Rabia, chief security officer of the sprawling facility, a 90-minute drive west from Tripoli on a road controlled by militias.

Three boats are moored nearby to carry off employees in case of attack. The company plans to install watchtowers and remote cameras, said Mustafa Ali Elfard, manager of the complex.

The plant supplies 10% of Italy’s natural gas imports via a pipeline running beneath the Mediterranean Sea. It is jointly owned by Libya’s National Oil Co. and Italy’s largest oil company, Eni SpA, which declined to comment on the plant’s security arrangements.

Italy’s defense minister Roberta Pinotti discussed the Islamic State’s threat in Libya with French and U.S. officials in Paris last month, saying outside military action required approval by a Libyan unity government.

Fears extend to Libya’s offshore oil industry, according to interviews aboard the Farwah production vessel, a facility in the Mediterranean about 60 miles off the coast. Migrants heading from Libya to Italy sometimes pass and ask for medical help, food or water, said workers, who worry whether the next group might be Islamic State militants in disguise.

One worker, recalling the date of the Paris attacks, said: “We fear they could do like they did Nov. 13.”

Islamic State surfaced a year ago in Libya with a deadly attack on a luxury hotel in Tripoli, followed by the beheading of 21 Coptic Christian Egyptians. The group, flying its black flag, later led a parade of fighters and vehicles rigged with heavy weapons through Sirte and launched its first oil-field assaults, driving out most expatriate workers of international oil companies.

Libya’s oil industry has so far withstood the attacks. It continues to transfer oil revenue around the country, enabling the payment of wages to public employees.

Islamic State doesn’t have control of Libyan oil fields to put them into production. In Syria and Iraq, by contrast, the group and its local allies pump oil and refine it for sale to the Syrian government in Damascus and to traders in Turkey.

For now, Islamic State is working to sabotage Libyan facilities, causing trouble for the economy and the few remaining European countries that rely on Libyan energy. A Libyan official said the group was likely using the attacks to seize gasoline for sale through black market networks that smuggle fuel to Tunisia and Malta.

The group has used social media and its magazine to recruit extremists with technical expertise to Libya, Mr. Shoukry said, suggesting it was only a matter of time before Islamic State tries to employ seized oil facilities to feed the oil market through the port in Sirte.

Libyan oil workers who are in the cross hairs of Islamic State say the threat isn’t far from their minds.

Not long ago at Mellitah, members of the plant’s staff were startled from their bunks one night by gunshots, prompting fears of an Islamic State attack. The facility is a maze of pipes and storage tanks loaded with natural gas that can easily ignite.

The shots turned out to be a gunfight between members of two local armed groups over a kidnapping.

Coming to work requires a steely resolve, one Mellitah worker said.

“Do I look scared?” he asked.

How to submit an Op-Ed: Libyan Express accepts opinion articles on a wide range of topics. Submissions may be sent to oped@libyanexpress.com. Please include ‘Op-Ed’ in the subject line.

- France to recognise Palestinian state in landmark UN declaration - July 25, 2025

- Libya and US explore $70 billion investment prospects - July 24, 2025

- UN envoy meets AU officials to align efforts on Libya - July 24, 2025