Have Libyans become Libyans?

When Greeks sailed from Thera (Santorini) in the 7th century BC, their encounter with the Libu tribes inadvertently named a nation. This historical footnote might seem trivial, but it illuminates Libya’s fundamental challenge: its identity was defined from the outside before it could define itself.

Throughout history, Libya’s name and nature have shifted like its desert sands. Under Ottoman rule (1551-1911), it was Eyalet-i Trablus-i Garb (Tripolitania), during Italian colonisation (1911-1943) it became “Libya” again, but on the ground, people identified with their regions, tribes, and local governance structures – a pattern that persists today.

My grandfather’s story illustrates this perfectly. In the 1940s, as our village’s religious scholar, he signed documents as “Ibrahim bin Ramadan al-Maghribi al-Khalifi al-Gharyani,” each name representing concentric circles of identity from village to district to prefecture. Tellingly, even in 1947, just four years before independence, “Libyan” wasn’t part of his identity markers.

The path to nationhood challenges our traditional narrative. The celebrated resistance against Ottoman and Italian rule wasn’t a unified national movement. Take Omar Al-Mukhtar’s resistance (1912-1931): whilst heroic, it was primarily centred in Cyrenaica. According to military records, most tribes fought only within their traditional territories, except for a few pivotal battles like Al-Hani and Al-Qardabiya.

Libya’s independence in 1951 came through international politics rather than national struggle. UN Resolution 289 (21 November 1949) and, crucially, Haiti’s delegate Emile Saint-Lot’s decisive vote, prevented the Bevin-Sforza partition plan. King Idris’s coronation on 24 December 1951 marked the birth of a nation that needed to be built from scratch.

The monarchy’s brief experiment with unity (1951-1969) gave way to Gaddafi’s 42-year rule, which attempted to forge national identity through force rather than reconciliation. His elimination of civil society and traditional power structures created an institutional vacuum that, ironically, reinforced the very regional and tribal bonds he sought to erase. When his regime fell in 2011, these historical fault lines resurfaced with renewed vigor.

Today’s Libya mirrors these historical fault lines. Recent data from Libya’s Bureau of Statistics shows the west still holds 65% of the population, whilst the National Oil Corporation confirms 80% of proven oil reserves lie in the east. The Great Man-Made River Authority reports 70% of water resources originate in the southern aquifers.

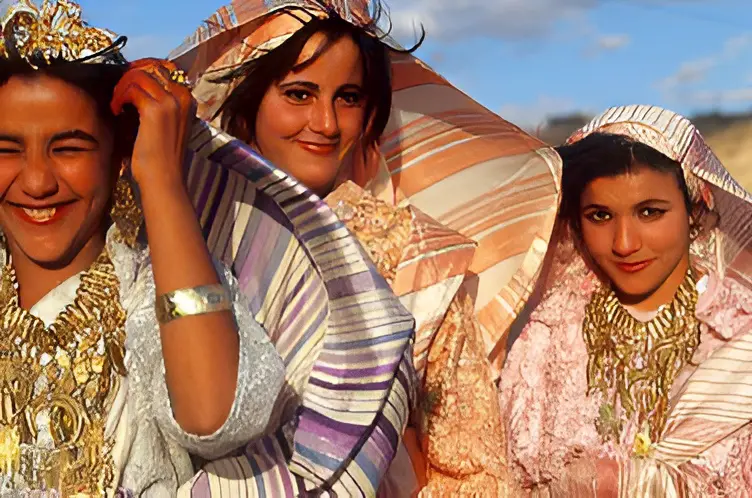

Unlike its neighbours Egypt and Tunisia, Libya encompasses five distinct societal groups, as documented in Dr Amal Obeidi’s 2001 study “Political Culture in Libya”: coastal urbanites (28% of population), agricultural communities (25%), agro-pastoral populations (20%), Bedouin tribes (15%), and oasis dwellers (12%). Each maintains distinct traditions whilst sharing space with Libya’s ethnic mosaic of Arabs, Amazigh, Tuareg, Tebu, and others.

The current crisis isn’t just political; it’s existential. Since 2014, the UN Refugee Agency reports over 200,000 Libyans remain internally displaced.

The country has two competing governments, split banking systems, and divided national institutions. Even shared symbols like the flag and national anthem (written by Tunisian poet Ahmed Khraief and composed by Egyptian Mohammed Abdel Wahab in 1951) are contested.

Despite possessing Africa’s largest oil reserves (48.4 billion barrels proven) and a small population (just under 7 million), Libya struggles to forge a cohesive identity. A 2023 World Bank report estimates $730 billion in frozen development potential over the past decade due to political instability.

There’s a telling story often shared in Libyan households: An angel offers two neighbours a wish, with the catch that whatever one receives, the other gets double. One neighbour, consumed by rivalry, wishes to lose an eye – ensuring his neighbour’s complete blindness. This parable captures Libya’s current predicament, where regional rivalry overshadows national interest.

The path forward requires three concrete steps. First, a decentralized governance model that gives regions control over local affairs while maintaining national unity on defense, foreign policy, and resource distribution. Tunisia’s 2014 constitution, which balanced central authority with regional autonomy, offers a useful template. Second, the establishment of a National Reconciliation Commission, modeled on South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission but adapted to Libya’s tribal context, to address historical grievances. Third, the creation of cross-regional economic zones that incentivise cooperation – imagine joint development projects linking Benghazi’s port facilities with Tripoli’s financial sector and the south’s agricultural potential.

Until Libyans can see themselves in each other – coastal urbanite in Bedouin, easterner in westerner, Arab in Amazigh – the question “Have Libyans become Libyan?” will remain painfully relevant. But the tools for transformation exist: Libya’s young population (median age 25) shows increasing willingness to transcend old divisions, as evidenced by the rise of cross-regional civil society organisations since 2011.

The nation’s future lies not in erasing these differences but in weaving them into a stronger national fabric – a tapestry where each thread retains its colour while contributing to a greater whole.

How to submit an Op-Ed: Libyan Express accepts opinion articles on a wide range of topics. Submissions may be sent to oped@libyanexpress.com. Please include ‘Op-Ed’ in the subject line.

- Trump’s Jerusalem Gambit: A Desperate Move That Could Ignite the Middle East - January 14, 2025

- Have Libyans become Libyans? - December 11, 2024